The year 2022 witnessed two historic events with lasting geopolitical implications. The first was Russia's invasion of Ukraine on February 24, which needs no explanation. The second, on October 7, the United States enacted a new series of export control regulations aimed at China's artificial intelligence (AI) and semiconductor industries. Although most Americans may not fully grasp the significance of the October 7 policy, it marked a turning point in U.S.-China relations and international politics.In many respects, the October 7 policy was narrowly focused, only limiting exports of specific advanced computer chips for AI applications and associated technologies for designing and manufacturing AI chips. However, the approach and rationale of the new regulations represented a significant departure from 25 years of U.S. trade and technology policy toward China in at least three ways.

A Pivotal Moment in China's Approach to Semiconductor Technology

First, instead of restricting exports of advanced semiconductor technology based on military end-uses or prohibited end-users, the new policy restricted them on a geographical basis for China as a whole.

Second, while previous U.S. export controls aimed to allow China to progress technologically but at a restricted pace to maintain a durable lead for the United States and its allies, the new policy actively degraded China's semiconductor industry's peak technological capability. Leading Chinese semiconductor firms such as Biren, YMTC, SMIC, and SMEE suffered significant setbacks.

Third, the policy aims to prevent China from achieving certain advanced performance thresholds in semiconductor technology in the future. Instead of raising the performance thresholds every few years as was done in the past, the Biden administration plans to maintain them at a constant level, causing the performance gap to widen over time as China lags behind. The October 7 policy and the ongoing U.S. efforts to convince key allies to join in represent a new landscape for the Chinese semiconductor industry, which had previously been advancing technologically, albeit unevenly.

China's response to the US export controls on semiconductors in October 2022 appeared relatively muted, but this was because China had already been working on eliminating US technology from its semiconductor supply chain for years. China's leadership viewed the semiconductor industry in national security terms, not economic terms, after the US imposed strict export controls on a major Chinese telecommunications company, ZTE, in April 2018. China believed that extreme US moves in the future were inevitable. Understanding how China adjusted its strategy in response to the ZTE sanctions is important to view China's response to the October 7 export controls. ZTE had illegally evaded US sanctions by selling telecom equipment containing US chip technology to Iran, and after a year of legal wrangling, pled guilty and paid a $1.2 billion fine in March 2017, but was caught again failing to abide by the terms of the settlement in early 2018.

The United States imposed sanctions and export controls on China's second-largest telecommunications company, ZTE, in April 2018 for repeatedly engaging in unlawful activity. The controls prevented ZTE from buying U.S.-designed semiconductors, causing its manufacturing and sales to stop. China's leadership reacted by commissioning research on its strategic technology vulnerabilities and making significant changes to its semiconductor policy. The shift was evident from speeches by Chinese leadership and the view that ZTE was a turning point. China's secrecy and evasiveness made it challenging to reach a firm conclusion about the decision-making process of China's most senior leadership.

China's Vulnerable Technology Chokepoints Revealed

In 2018, China's Ministry of Science and Technology's official newspaper, Science and Technology Daily, published a series of articles that highlighted the country's most vulnerable technology chokepoints. These are technologies on which China is heavily reliant on U.S., Japanese, and European suppliers, and for which it is difficult to produce Chinese alternatives.

The articles provide rare specifics on the phrase "key and core technologies are controlled by others," which has become increasingly important in Chinese leadership speeches and state-run media since April 2018. There are 35 identified chokepoints, including seven that relate directly to the semiconductor industry, covering almost every aspect of the semiconductor value chain.

An analysis by Ben Murphy from the Center for Security and Emerging Technology noted the significance of the publication, as it provides insight into China's strategic thinking about the technologies it is most vulnerable to losing control over.

Chinese Leaders' Speeches Following the ZTE Crisis in April 2018

After the ZTE crisis in April 2018, Chinese leaders began to emphasize the urgency of reducing China's vulnerability to US economic pressure and strengthening its position in strategic technologies. Dr. Tan Tieniu, in a speech to senior Chinese leadership in November 2018, stressed the importance of independent, controllable core technologies and the need to learn from the ZTE disaster. This marked a turning point in China's strategic thinking on semiconductors, as industrial policy goals merged with national security priorities. General Secretary Xi echoed this sentiment in his speeches, emphasizing the need for self-reliance and reducing dependence on foreign technology. The Roadmap of Major Technical Domains for Made in China 2025, published in 2015, included the goal of replacing imports with Chinese-made products in key industries by 2025. China's strategy extends beyond freeing itself from technological dependence on the US to ensuring that the US is dependent on China. Xi has stated that China must tighten international production chains' dependence on China, forming powerful countermeasures and deterrent capabilities by artificially cutting off supply to foreigners.

Alterations in China's Policy on Semiconductors

The Chinese semiconductor policy changed after the ZTE event, as the Chinese government and private sector began stockpiling chips and chip-making equipment to hedge against potential future restrictions. The $21 billion National Integrated Circuit Industry Fund was renewed with an additional $35 billion, and local governments established 15 semiconductor investment funds worth an additional $25 billion. The Chinese government shifted subsidies to prioritize the growth of domestic semiconductor capacity and alternatives to foreign, especially U.S., technology dependencies. Document No. 8, published in July 2020, provides financial and other support measures to promote the semiconductor sector, and the 14th 5-year economic plan, covering the years 2021-2025, declares the semiconductor industry to be a top technology priority. Xi's thinking is reflected in the final, public version of the 5-year plan adopted in October 2020, which declares technological self-sufficiency a strategic pillar of national development. Other events during the Trump administration also weighed heavily, including U.S. sanctions on Huawei and Fujian Jinhua, the Dutch government blocking exports of Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography machines, and the U.S.-China Trade War.

The Challenge of China's Industrial Policy After October 7

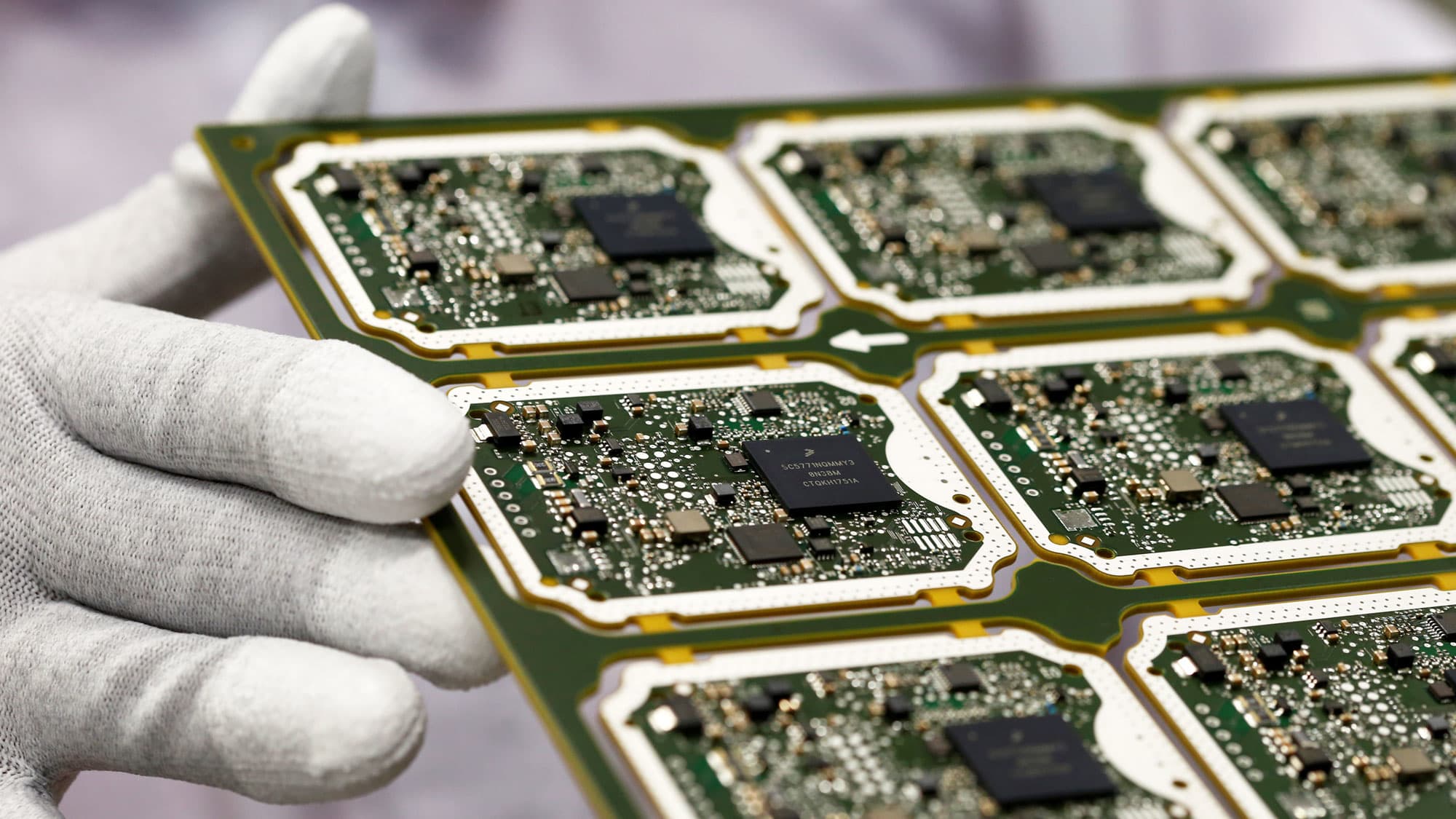

The global semiconductor value chain is complex, with some companies playing diverse roles and others being highly specialized. No single company or country is currently capable of performing all roles in the value chain for all types of semiconductors required for a modern economy. The October 7 export controls of the US, Japan, and the Netherlands pose a significant challenge to China's industrial strategy for semiconductors. The export controls target China across the semiconductor value chain, from design to manufacturing equipment, and cover nearly every type of advanced chip-making equipment. This means that China's dreams of self-reliance will face multiple technological barriers that China must overcome simultaneously to benefit financially. Information asymmetry and crony capitalism pose traditional challenges for industrial policy, but the traditional industrial policy mechanism for solving these two challenges is "export discipline." However, China's post-WTO industrial policy approach relies more on foreign firms owning production facilities in China, and it has been instrumental in the growth of many industries in China, including semiconductors.

Analyzing China's Strategic Goals in Addressing the Implications of October 7 Policies

China's strategic objectives after October 7th are centered on limiting their exposure to foreign economic pressure, deterring future economic pressure from the US and its allies, increasing international economic dependence on China, and gaining economic and security benefits from artificial intelligence (AI). The risk of an all-out semiconductor embargo by the US and its allies is a major concern for China, as the country imported more than $350 billion worth of semiconductors in 2020, which is more than its imports of oil. In addition to retaliation, China's central strategic aim is to gain and preserve the strategic benefits of AI and semiconductors, rather than punishing the US. By increasing foreign dependence on China, the country seeks to have strengthened supply-side coercive power. China has become an important supplier of chips in the world, responsible for 9% of global production in 2020, but the Chinese share of global chip production declined significantly during the Covid-19 lockdown years. Therefore, China's dominance of rare-earth metal mining and refining capacity is considered its most frequently discussed source of near-term coercive power.

Updated Strategy: Utilizing Both New and Old Tactics

China has employed a mix of fresh approaches and intensified efforts on existing ones, while the overall strategy and objectives remain largely unchanged. This segment concentrates on five key tactics that merit examination, although there are more aspects of China's endeavors that warrant attention. These tactics are as follows:

- Persisting to gain access to foreign technology by circumventing new restrictions

- Striving to create a divide between the United States and its allies

- Engaging in industrial espionage and recruiting talent to obtain foreign technology

- Using pressure on Chinese companies to procure domestically and eliminate American suppliers

- Retaliating against the United States and its allies

Bypassing Controls to Access Foreign AI Technology

The October 7 export controls placed restrictions on four categories of exports, with the controls on chip-making equipment being the easiest to enforce. However, AI chips are small and lightweight, making them susceptible to smuggling. Though no confirmed cases of post-October 7 AI chip smuggling have been reported, it is a well-known practice in China. The US government suspects that China is attempting to evade the controls by smuggling AI chips, but this is difficult to accomplish at the needed scale for training large AI models.

While corporate export compliance through “know your customer” and other measures is much easier with a small set of hyperscale cloud operators and datacenter providers, China can aggregate many small purchases through shell companies. However, this would be a slow and laborious process. The US government has stepped up intelligence community support for export controls enforcement, which should increase the likelihood of catching smugglers.

China has also begun cracking down on foreign consulting firms that support corporate due diligence efforts, making it harder for US firms to gather information that would help with de-risking efforts. Additionally, Chinese AI companies can legally import the chips to their subsidiaries in other countries and allow Chinese programmers in China to access the computing capacity via the cloud.

Lastly, Chinese AI companies can absorb the performance hit of using chips that comply with the export control performance thresholds. Nvidia, for example, has released reduced interconnect variants of its best AI chips that can legally be exported to China, with an estimated overall performance penalty of less than 10 percent. This is tolerable for well-resourced Chinese AI companies and national security organizations.

Attempting to Create a Divide Between the United States and Its Allies

The vast majority of global semiconductor equipment sales are generated by four countries: the United States, Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea. When the United States announced export controls on October 7th, Chinese companies began courting equipment makers in the other countries, while the Chinese government pressured them to not comply with the US controls. China made threats to the Netherlands and Japan, but since they have already made plans to join the US in placing export controls on advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment, the real target of these threats is likely South Korea, Germany, and the European Union.

South Korea is particularly significant as a small but sophisticated player in the global semiconductor manufacturing market, with roughly 5 percent global market share. South Korean equipment companies are also more advanced than those of China, and South Korea has deep linkages to the Chinese semiconductor industry. However, the October 7 export control policy was a massive setback to Chinese competitors, benefiting South Korean memory chipmakers Samsung and SK Hynix. These companies are now planning to shift their production capacity expansion back to South Korea, which is forecast to overtake China as the world’s largest buyer of semiconductor manufacturing equipment next year.

Both China and the United States are trying to sway South Korea's government to their side in the export controls dispute, but the United States is likely to have the edge due to South Korea's recent efforts to pursue closer ties with both the US and Japan. The Netherlands and Japan have already joined the US in placing export controls, and China's threats are aimed at swaying South Korea, Germany, and the European Union to not follow suit.

Acquiring Foreign Technology Through Industrial Espionage and Talent Poaching

Obtaining foreign technology through industrial espionage and talent recruitment has been a longstanding practice in the semiconductor industry. According to a declassified CIA report from 1977, the Soviet Union's efforts to steal and copy semiconductor manufacturing equipment technology were a major concern for the US government. However, in recent years, some industry players have questioned the effectiveness of these tactics, given the importance of tacit knowledge among skilled organizations and workers.

Despite these concerns, China continues to engage in industrial espionage to acquire technology from foreign companies. For instance, ASML, a Dutch lithography equipment firm, has faced thousands of security incidents each year, leading to increased spending on cybersecurity and other protective measures. Chinese attempts to steal technology from Taiwan's semiconductor industry are also a major concern, as Chinese firms are known to set up shell companies in Taiwan and recruit workers to transfer knowledge to China.

To combat this threat, Taiwan has introduced new laws to strengthen the security of its semiconductor industry, including setting up a dedicated economic espionage judicial system to speed up trials and convictions. Chinese fabs have also been known to structure their manufacturing operations to run foreign and Chinese-built equipment side by side, allowing Chinese workers to provide feedback to Chinese equipment companies on how to improve their designs based on their experience with foreign systems.

Encouraging Chinese Companies to Prioritize Domestic Suppliers and Reduce Dependence on American Products

Chinese firms have advantages in advancing their level of semiconductor equipment technology due to state financial support and the knowledge of foreign firms’ successful technological paths. However, their disadvantage is that their competitors' equipment is already established with superior performance, making it difficult for Chinese firms to gain market share. To break this cycle, Chinese leaders aim to pressure Chinese fabs to buy Chinese equipment. Although China recognizes that it cannot build an all-Chinese semiconductor supply chain overnight, it is seeking to bolster domestic demand and supply simultaneously by focusing on legacy chips and chipmaking equipment. The US government's actions may be more influential than the Chinese government's actions in persuading Chinese firms to avoid buying American unless necessary. In short, China is exploring a strategy of fully independent manufacturing in two steps, emphasizing establishing linkages between Chinese players in all segments of the value chain.

Taking Revenge on the United States and its Allies

China is retaliating against the United States and its allies in two ways. Firstly, it is using its anti-trust enforcement regime to block almost all mergers and acquisitions involving U.S. semiconductor industry firms. This is a significant shift from previous practice, as almost all prohibitions, conditional approvals, and abandonments over the past decade have occurred in technology sectors important to China's national growth, such as semiconductors. Secondly, China has initiated a cybersecurity review of Micron, the largest U.S. memory chipmaker, which could result in its exclusion from the Chinese memory market and a potential loss of $3.3 billion in annual sales. China's use of anti-trust measures and cybersecurity reviews are more significant retaliatory responses than it has taken in the past. China may widen its retaliatory measures to additional areas, but it appears to have calculated that such measures would do more harm than good.